- No precedence exists for the copper antennae tilt swords from mature harappan sites

- No precedence exists for the cart burials

- Sanauli finds are efinitely a bullock-cart, round wheels too heavy to be pulled by horses. Word for bullock cart in Sanskrit is from Dravidian and replaced IE anas.

- Daimabad late harappan finds definitely show it was a bullock cart.

- Sanauli burials are 100% a part of the OCP culture, OCP vases found there

- Also confirms Copper Hoards are part of OCP culture?

- Iconography of bulls found in the burials but no horses or horse bones, confirms they are bullock carts

- Parpola suggests BMAC influence/origin for the swords

- Corrects a lot of his grossly incorrect takes from The Roots of Hinduism. No longer believes that Catacomb is Proto Iranian. Does not believe Abashevo is Proto Indo Aryan, but that PIA was Fedorovo/Eastern Andronovo while Srubnaya was Proto Iranian.

- He points out that post-urban BMAC settlements are surrounded by Andronovo pastoralist campsites but south of this region, neither Andronovo pottery, nor its barrows are found. So logical assumption is Aryans adopted BMAC culture and continued their southward spread in the garb of this BMAC culture.

- Thinks a wave of Proto Indo Iranians came to India from the Petrovka culture, a Sintashta successor, and that these PII are responsible for the Sanauli finds (extremley implausible). Then these Indo Aryans introduced a magic/tantra based pre-Atharvavedic cult.

He slays the foe and wins the spoil who worships Indra and Agni, strong and mighty Heroes, Who rule as Sovereign over ample riches, victorious, showing forth their power in conquest - Rigveda 6.60.1

Thursday, 27 October 2022

Sanauli Chariots?

Wednesday, 26 October 2022

The Sejma-Turbino Transcultural Phenomenon and the Spread of the Uralic Languages

Ainash Childebayeva, Fabian Fricke, Sergej Kuzminykh, Wolfgang Haak:

The Sejma-Turbino (ST) “transcultural” phenomenon is associated with Bronze Age sites throughout Eurasia dating to the time period between the 22nd to 17th centuries BCE. ST objects are found across the Eurasian continent, spreading from Finland to Mongolia, and the cultural complex is characterized by metal objects that have a unique petal shaped side piece. The origin of the ST phenomenon has not been determined. However, based on the presence of metals, such as tin and copper in ST objects, Altay and Sayan mountains have been hypothesized. No ST associated settlements are known, and the only distinguishing characteristic of the culture is the presence of high-quality metal objects. The spread of Uralic protolanguage is hypothesized to have occurred through the ST network, which is suggested by the time of disintegration of Proto-Uralic.

Here, we are presenting genomic data from nine individuals, eight males and one female, from the ST associated site Rostovka located on the river Om, 15km away from Omsk, Russia, and excavated in 1966-1969. Elaborate artifacts found at the site made it famous among the archaeologists and the scientific community in general. The majority of the graves found at the Rostovka burial site contain bronze ST objects, as well as stone molds for casting bronze objects, stone spearheads and armory. Based on the genome-wide SNP data, we found that the Rostovka individuals vary widely with regards to their genetic profile, ranging between the ancestry maximized in North Siberians and the local Sintashta-associated individuals, mirroring the geographic spread of the ST phenomenon. The presence of the N-L392 Y-haplogroup in the sample further supports the link between ST and the spread of the Uralic languages. This is the first study to report genetic data for individuals associated with the ST trans-cultural phenomenon and its potential link to the spread of Uralic languages across the Eurasian forest steppe.

See also,

Drastic demographic events triggered the Uralic spread

The widespread Uralic family offers several advantages for tracing prehistory: a firm absolute chronological anchor point in an ancient contact episode with well-dated Indo-Iranian; other points of intersection or diagnostic non-intersection with early Indo-European (the Late Proto-Indo-European-speaking Yamnaya culture of the western steppe, the Afanasievo culture of the upper Yenisei, and the Fatyanovo culture of the middle Volga); lexical and morphological reconstruction sufficient to establish critical absences of sharings and contacts. We add information on climate, linguistic geography, typology, and cognate frequency distributions to reconstruct the Uralic origin and spread. We argue that the Uralic homeland was east of the Urals and initially out of contact with Indo-European. The spread was rapid and without widespread shared substratal effects. We reconstruct its cause as the interconnected reactions of early Uralic and Indo-European populations to a catastrophic climate change episode and interregionalization opportunities which advantaged riverine hunter-fishers over herders.

As well as,

Radiocarbon Chronology of Complexes With Seima-Turbino Type Objects (Bronze Age) in Southwestern Siberia

Abstract

This paper discusses the chronology of burial grounds containing specific Seima-Turbino type bronze weaponry (spears, knives, and celts). The “transcultural” Seima-Turbino phenomenon relates to a wide distribution of specific objects found within the sites of different Bronze Age cultures in Eurasia, not immediately related to each other. The majority of the Seima-Turbino objects represent occasional findings, and they are rarely recovered from burial grounds. Here, we present a new set of 14C dates from cemeteries in western Siberia, including the key Asian site Rostovka, with the largest number of graves containing Seima-Turbino objects. Currently, the presented database is the most extensive for the Seima-Turbino complexes. The resulting radiocarbon (14C) chronology for the western Siberian sites (22nd–20th centuries cal BC) is older than the existing chronology based on typological analysis (16th–15th centuries BC) and some earlier 14C dates for the Seima-Turbino sites in eastern Europe. Another important aspect of this work is 14C dating of complexes within specific bronze objects—daggers with figured handles—which some researchers have related to the Seima-Turbino type objects. These items are mostly represented by occasional finds in Central Asia, however, in western Siberia these have been recovered from burials, too. The 14C dating attributes these daggers to the end of the 3rd millennium cal BC, suggesting their similar timing to the Seima-Turbino objects. Further research into freshwater reservoir offsets in the region is essential for a more reliable reconstruction of the chronology of the Seima-Turbino phenomenon and the daggers with figured handles.

Tuesday, 25 October 2022

Uralic loans, BMAC substratum and agricultural terms of Indo-Iranian

Some important papers that discuss the three different possible loaning events of Indo-Iranian. It's well known that Indo-Iranian (henceforth, Aryan) had a limited agricultural vocabulary, and skipped many of the agriculture-related semantic shifts that characterize PIE > Proto-European as the livestock breeding Yamnaya shifted to a more farming culture after contact with the European Neolithic. Fatyanovo-Balanovo, the pre-Proto-Aryan culture, mostly survived of foraging and livestock breeding, with very little to no macrofossil evidence for any kind of agriculture, though some slash and burn has been suggested based on circumstantial evidence. This means it's important to pay close attention to the agricultural vocabulary of Aryan, since this would mostly have picked up from one of the many farming oriented Turan Neolithic societies in Central Asia, or later from the Harappans or Elamites. We also know that it's pretty likely that the Proto-Aryans (Abashevo? Sintashta-Petrovka?) were in direct contact with the Proto-Uralics (Sejma-Turbino Metallurgists?) and there is clear evidence of borrowings from Proto-Aryan into Uralic, though the reverse is less studied, and even lesser studied are possible Proto-Iranic and Proto-Indic borrowings in Uralic, as well as parallel borrowings by different branches of Uralic. Regardless, the Uralic borrowings are certain, and merit a review paper of their own.

The three kinds of loaning events in Aryan likely are

1) Into/from Uralic?

2) From BMAC/Turanian Neolithic?

3) From Dravidian/Language X into Indo-Aryan & Elamite > West Iranian?

The first one offers the best overview on the Uralic situation.

Indo-Iranian borrowings in Uralic : Critical overview of sound substitutions and distribution criterion

This dissertation discusses the Indo-Iranian loanwords in the Uralic languages. The loanwords that have been suggested in earlier research are critically analyzed and commented based on modern views of Uralic and Indo-Iranian historical phonology and etymology. The etymologies are analyzed on the basis of the general methods of loanword research: arguments of phonology, distribution and semantics are taken into account. In addition to the analyzis of older etymological proposals, also some new etymologies are presented. Also the research history of the topic is discussed. The aim of this study is to establish rules for the sound substitutions and bring new light to the relative chronology of the loanwords. Because the phoneme systems of Proto-Indo-Iranian, Proto-Iranian and later Iranian languages were very different from those of Proto-Uralic and its daughter languages, the phonemes of the Indo-Iranian donor languages have been substituted in various ways in the Uralic languages. Differences reflect both conditional developments (different substitutions in different environments) and chronological differences, and it is often difficult to distinguish between the two.

The second paper by Alexander Lubtosky reviews the substratum (collection of possible non-Indo-European origin words) in Aryan and lists out likely/unlikely inherited vocab, as well as the basic laws for establishing non-IE words in Aryan, and possible Wanderworts.

In my paper, I shall apply this methodology to the Indo-Iranian lexicon in search of loan words which have entered Proto-Indo-Iranian before its split into two branches. As a basis for my study I use the list, gleaned from Mayrhofer's EWAia, of all Sanskrit etyma which have Iranian correspondences, but lack clear cognates outside Indo-Iranian. The complete list of some 120 Indo-Iranian isolates is presented in the Appendix. The words of this list are by default characterized by the first of the above-mentioned criteria, viz. limited geographical distribution, but this in itself is not very significant because thelack of an Indo-European etymology can be accidental: either all other branches have lost the etymon preserved in Indo-Iranian, or we have not yet found the correct etymology. Only if aword has other features of a borrowing, must we seriously consider its being of foreign origin.The analysis of phonological, morphological and semantic peculiarities of our corpus will be presented in the following sections, but first I would like to make two remarks.

I use the term substratum for any donor language, without implying sociological differences in its status, so that substratum may refer to an adstratum or even superstratum. It's possible that Proto-Indo-Iranian borrowed words from more than one language and had thusmore than one substratum.Another point concerns dialect differentiation. In general, we can speak of language unity as long as the language is capable of carrying out common innovations, but this does not pre-clude profound differences among the dialects. In the case of Indo-Iranian, there may have been early differentiation between the Indo-Aryan and Iranian branches, especially if we assume that the Iranian loss of aspiration in voiced aspirated stops was a dialectal feature which Iranianshared with Balto-Slavic and Germanic (cf. Kortlandt 1978: 115). Nevertheless, Proto-Indo-Iranian for a long time remained a dialectal unity, possibly even up to the moment when the Indo-Aryans crossed the Hindukush mountain range and lost contact with the Iranians

The last paper is really a chapter by Martin Kümmel for the book 'Language Dispersals Beyond Farming' and so specifically takes a look at the agriculture related vocabulary of Aryan.

Agricultural terms in Indo-Iranian

The article investigates the agricultural lexicon of Indo-Iranian, especially its earlier records, and what it may tell us about the spread of farming. After some general remarks on “Neolithic” vocabulary, a short overview of the animal husbandry terminology shows that this field of vocabulary was evidently well established in Proto-Indo-Iranian, with many cognate terms. Words for cattle, horses, sheep and goats are well developed and mostly inherited, while evidence for pigs is more limited, ad the words for donkey and camel look like common loans. A more extensive discussion of plant terminology reveals that while some generic terms for grain are inherited, more specific words for different kinds of cereals show few inherited terms and/or irregular variation, and the same is even clearer for pulses and some other vegetables. The terminology for agricultural terminology is largely different from that of most European branches of Indo- European. The conclusion is that the cultural background behind these linguistic data points to spreading of a mainly pastoralist culture in the case of Indo-Iranian.

Thursday, 20 October 2022

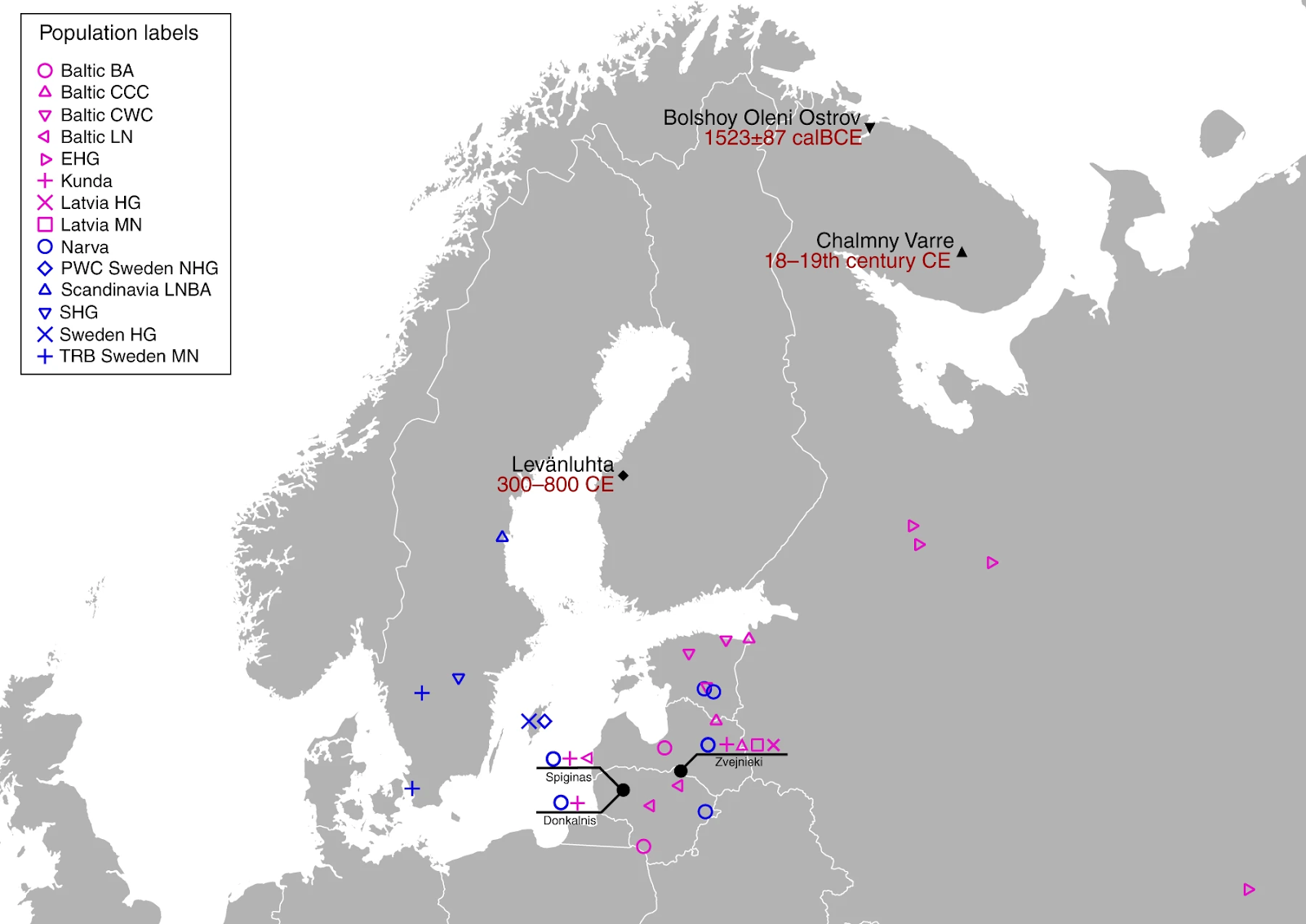

The genomic ancestry of the Scandinavian Battle Axe Culture people and their relation to the broader Corded Ware horizon

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2019.1528

We generated and analysed genome sequence shotgun data from 11 individuals originating in northeastern Europe datedto 3300–1660 cal BCE (electronic supplementary material,table S1). Five individuals were excavated from CWC contexts:two from Obłaczkowo, Poland, one from Karlova, Estonia,and two from the CWC-related BAC burial Bergsgraven in Linköping, Sweden. The six additional individuals werefrom other archaeological contexts in Sweden: five from megalithic burial structures primarily associated with Funnel BeakerCulture (FBC) (two from Rössberga in Västergötland and threefrom Öllsjö in Scania) and one from a Pitted Ware Culture(PWC) context (Ajvide on Gotland). Radiocarbon dating showed that the three individuals from the Öllsjö megalithic tomb derived from later burials, where oll007 (2860–2500 calBCE) overlaps with the time interval of the BAC, and oll009and oll010 (1930–1650 cal BCE) fall within the Scandinavian Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S1 and figure S2). Genome-wide sequence coverages range from 0.1 to 3.2×, and the sequence data for all individuals exhibit characteristic properties ofancient DNA: short fragment size and cytosine deamination at the ends of fragments (e.g. [24]) (table 1; electronic sup-plementary material, figure S5). Estimates of mitochondrialcontamination [25] were low, less than 2% for all 11 individuals, as was the estimated nuclear contamination on theX-chromosome in males [26,27] (less than 1.2%) (table 1; electronic supplementary material, table S3). Five individuals were genetically determined to be males, and six were females,based on the fraction of sequence fragments mapping to thedifferent sex chromosomes [28] (table 1)

The other individuals who were contemporary with BAC but had unclear cultural contexts, and who were buried in the Ölljsö megalith constructed many hundred years earlier (oll007), or found as a stray find (Ölsund) [9], show the same genetic profile as individuals from typical BAC contexts in other parts of Sweden

The best fitting two-source model was Funnelbeaker (FBC) + Yamnaya (YAM) (p = 0.86), while YAM + PWC (Pitted Ware Culture) would also fit the data (although trending toward low p-values; p = 0.07). These observations suggest that—to our statistical resolution—a direct PWC contribution to BAC is not needed in a model, but actual PWC admixture might have been small or there may have been indirect PWC contributions through PWC first mixing with FBC [34] who later contributed ancestry to BAC. Notably, using only the CWC population as the single source for BAC was consistent with the data in all cases (p > 0.05, except when using CWC-associated individuals from Latvia, CWC_LV). The BAC groups fit as a sister group to the CWC-associated group from Estonia (CWC_EE, electronic supplementary material, figure S8) but not as a sister group to the CWC groups from Poland (CWC_PL, figure 3) or Lithuania (CWC_LT, electronic supplementary material) (|Z| > 3), indicating some differences in ancestry between these CWC groups and BAC.

Funnelbeaker tombs were reused by the Battle Axe Culture.

The Scandinavian Middle Neolithic megalithic tombs are associated with the FBC. However, their reuse, indicated by artefacts common to the BAC and later periods, has been noted [17]. The oll007 individual, buried in the FBC-associated Öllsjö megalithic tomb, but radiocarbon dated to the time period of the BAC, is genetically very similar to individuals from BAC contexts (e.g. Bergsgraven and Viby). Thus, although archaeologically the reuse of megalithic tombs was assumed earlier [17], our study may be the first direct link (using genetics) showing that indeed FBC-associated megalithic tombs were used as burial places also for the people of the BAC. This could possibly also extend to the Danish Single Grave Culture (SGC) [49], as RISE61 [2], a male buried in the Kyndeløse passage grave and with a radiocarbon date overlapping with the BAC/CWC/SGC time period, also displays some steppe ancestry.

Supplementary information: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/action/downloadSupplement?doi=10.1098%2Frspb.2019.1528&file=rspb20191528supp1.pdf

More here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.24079

Monday, 17 October 2022

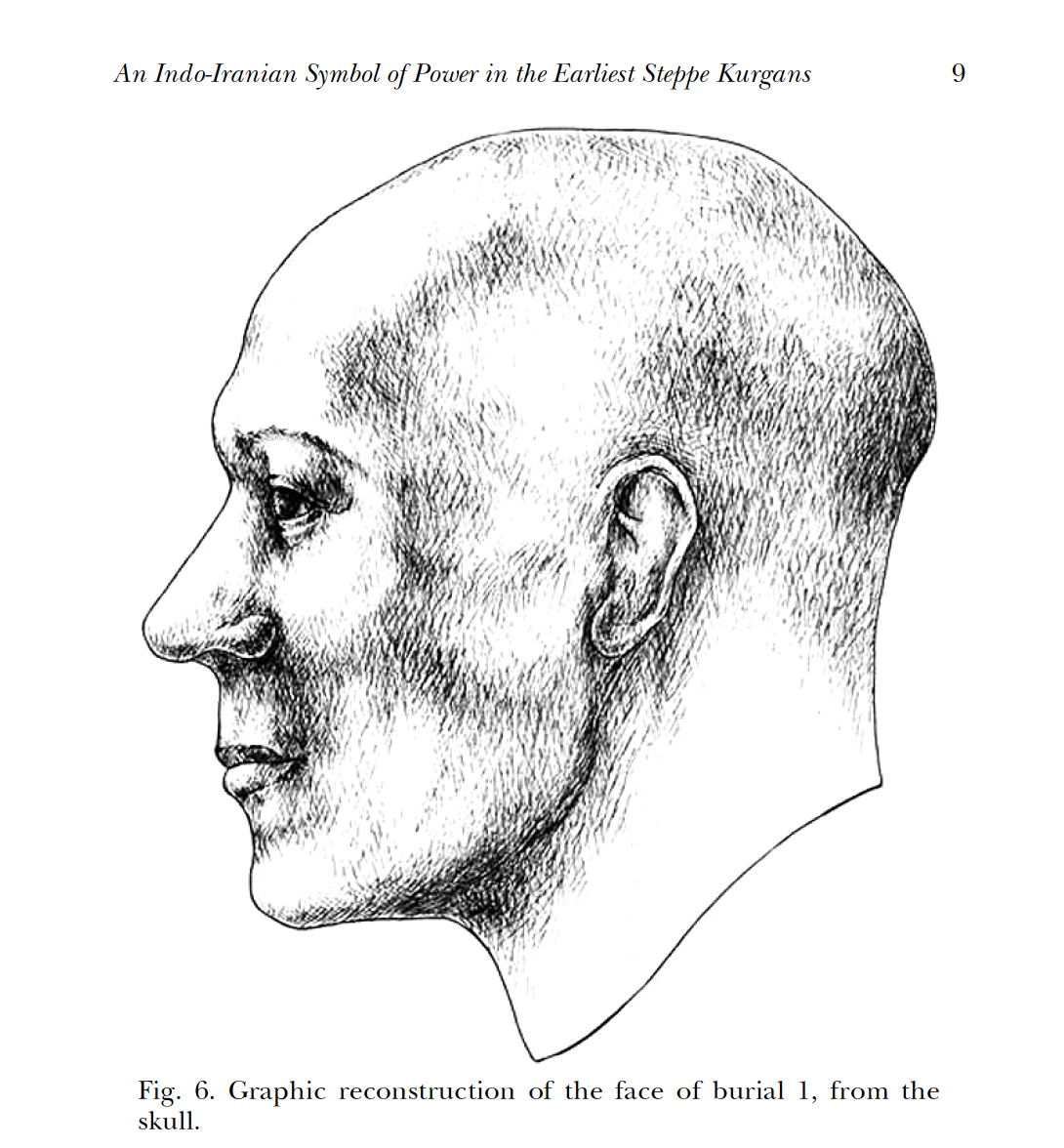

An Indo-Iranian Symbol of Power in the Earliest Steppe Kurgans

https://www.academia.edu/3836804/An_Indo_Iranian_Symbol_of_Power_in_the_Earliest_Steppe_Kurgans

The diameter of kurgan 4 was about 21 meters, and the modern height of the mound is 0.85 m. Central grave 1 was dug into the clay subsoil. The clay taken out of the pit was spread around it in the shape of two platforms. In the center of the northern platform, outside the central grave pit, a secondary accompanying burial was made (Fig. 3) Here a mature female was laid on her back with her knees raised and her head towards the east. Her feet were abundantly powdered by ochre. Her body was covered when the mound was constructed. The principal burial, grave 1, was in a pit measuring 2.8 x 1.7m. It was oriented with its long axis NW-SE. The pit floor was 1.07m beneath the original ground surface. A mature male was laid on his back, originally with his knees half-bent and raised vertically. Later they fell to the right side. The skull was found fallen forward on the chest. The right arm was stretched out along the body; the left was a little bent at the elbow. The body lay across the long axis of the grave, with the head oriented ENE. The facial area of the skull was abundantly painted with red ochre, the pelvis and feet were less painted. A fibrous organic bedding about half a centimeter thick was under the skeleton. The structure of the fibers suggests that the bed was made of either narrow strips of bark fastened together or, more probably, reed mats

Specialist A. Khokhlov of Samara State Pedagogical University determined that the skeleton was of a male 35-40 years old (Fig. 5). His legs were unusually long, especially the lower legs. His forearms also were long. He stood more than 176cm. tall, which is taller than the average height of modern European men. Detailed examination of the joint surfaces of the skeleton led A. Khohlov to the conclusion that the Kutuluk man was unusually active, particularly in walking and/or running.

Calibration of these samples firmly dates the Kutuluk grave to 3100-2800 BC, with the most probable date between 3000 and 2900 BC. The first half of the 3rd millennium BC corresponds well with the dates of other Late Yamnaya culture complexes. A massive copper object was found in the crook of the left arm of the Kutuluk man. It is 48.7cm long overall and weighs 750gms. The handle part is 12.6cm long. The handle is rectangular with polished edges. Some traces indicate that the handle was wrapped with an organic material, probably a leather strap up to 7mm wide. The butt of the handle is semiovoid in plan and broadened in section, giving it extra weight.

Some characteristics of the Vajra.

Among the first to describe the vajra as a cudgel-like weapon was L.S. Klein (Klein 1985: 75). The vajra was tetrahedral (RV 4.22.2]. It had a cow skin-strap (RV 1.121.9). It could be ground (RV 1.55.1). But it had one more very important characteristic—it glistened: All the above-mentioned characteristics of the vajra are most detailed and exact. If we summarize them, we get a description of a weapon used to deliver heavy blows, fracturing and splintering bones, like a cudgel. It had a cow-hide strap. The vajra was made of metal and glistened like gold under the sun, so it must have been made of polished copper or bronze. It was tetrahedal, or four-faced, like the diamond-sectioned Kutuluk cudgel-scepter. Among all the weapon types of Bronze Age, over a period of one and a half thousand years, only the Kutuluk find corresponds to the description of the vajra in the RigVeda. Even the leather strap braiding the handle is rather pertinent in this case.

Similar finds by Falk in the OCP copper hoards.

On the territory of Hindustan in the Ganges-Yamuna Doab are found copper hoards of the 2nd millennium BC, the post-Harappan period. They are connected with the Ochre Colored Pottery culture, which occupied a territory sometimes linked with that of the early Indo-Aryans. Falk noted that the copper hoards included so-called bar-celts, which by their shape and size absolutely coincide with Kutuluk cudgel-scepter. “The vast majority measure about half a meter, and weigh about 1.5kg (Hami, Bihar) or 2.2kg (Gungeria). Therefore I propose to interpret these pieces of copper as clubs, used to kill an adversary either by hitting or by being thrown.” (Falk 1993: 200]. Falk considers the bar-celts to be the material expression of the vajra, the divine weapon of Indra (Falk 1993: 201).

Possible prototypes of the Yamna cudgel?

Prototypes for this specific type of weapon have not been found among earlier Early Bronze Age kurgans, but large antler clubs and polished stone mace-heads of various kinds are wellknown weapons of the Eneolithic period (5000-3500 BC) in the Middle Volga region. These might also have been hurled in battle. They provide earlier examples of weapons that functioned in a way similar to the Kutuluk cudgel-scepter

Wednesday, 12 October 2022

A Study on the Painted Grey Ware

https://www.academia.edu/38059410/A_Study_on_the_Painted_Grey_Ware

Key points from the paper: (Just read Summary section if short on time)

- Bara style pottery has clear roots in Indus/Harappan and Sothi-Siswal pottery of Ghagra valley.

- PGW is localized to Western Ganga (WG) valley and Eastern Ghagra. PGW is a new ceramic style with closed kiln firing and is not related to Bara style pottery despite some concurrent finds of fragments at some sites.

- Eastern Ganga (EG) valley was occupied by the EG Black Ware tradition (BRW, BSW). EGBW developed from indigenous traditions of Black Ware (carbonized layer by plants to give black color) that go back to 5th millenium BCE.

- NBPW is divided into early and late phases: 1st phase is 6th-3rd century BCE, second is 3rd-1st century BCE.

- BRW & BSW dispersed across WG valley during late 2nd millenium, replacing Bara-OCP (Ochre Colored) tradition.

- EGBW evolved into NBPW, PGW is not proto-type of NBPW. EGBW uses open kiln firing technique, so different tech than PGW.

- PGW was perhaps Aryans + EGBW (indigenous/native tradition that had spread to the WG/South Rajasthan)

- NBPW originates as mix of PGW closed kiln firing technique but in geography of EGBW.

- Lot more radiocarbon dating needed to fix relative internal chronology, currently we're guesstimating a bit based on these dates.

- BB Lal's date of 600 BCE for the NBPW phase as Hastinapura is perhaps incorrect, as the coarse pottery found there belongs to late NBPW, not early NBPW. This would also effect the 800 BCE date given for the PGW phase as Hastinapura.

PGW is apparently distinguished from the Bara‐style pottery (Figure 8). The Bara‐style pottery is composed of pots, bowls and dish‐on‐stands whose proto‐types can be found in the Harappa‐style and Sothi‐Siswal pottery of the Urban Indus period (Uesugi and Dangi

2017). They were fired in an oxidised condition. The painting motifs of this pottery are also derived from the Harappa‐style and Sothi‐Siswal‐style pottery. PGW is comprised of straight‐sided bowls, hemispherical bowls and shallow bowls/dishes which are totally absent in the Bara assemblage. The firing technique in a reduced condition using closed kilns is also an element showing a difference between PGW and the Barastyle pottery. The painting motifs of PGW, which consist of geometric motifs, also exhibit a clear difference from the Bara‐style pottery. Therefore, these two styles of pottery have no stylistic and technological similarities.

Hence, it seems that the spread of NBPW over the western Ganga Valley and the Ghaggar Valley occurred predominantly during the Late NBPW phase, which can be dated between the fourth/third century BCE and the beginning of the Christian Era.

In the western Ganga Valley and northern Rajasthan, the black ware industry is identifiable as having an independent phase between the Bara‐OCP phase and the PGW phase and as continuing to the following PGW‐dominant phase (Gaur 1983). Even in the Ghaggar Valley, BRW and BSW are known to be associated with PGW (Figure 9: 1‐19), although there is no independent phase of BRW and BSW in this region. These pieces of evidence imply that the black ware industry and PGW had some relations. The examinations made above indicate that PGW and BRW/BSW share some common traits in the formal assemblages and have different features in the morphological and technological aspects. The morphological similarty between some of the shallow bowls/dishes of PGW having straight sides (Figure 3: 16 ‐ 18; Figure 5: 17 ‐ 22) and that of BRW/BSW (Figure 9: 7 ‐ 10, 14 ‐ 16, 22, 23, 31, 32) exhibits the interaction between these two types of ceramics and the influence from BRW/BSW to PGW.

The region of origin of PGW has not been specified, but the dense distribution of PGW sites in the Ghaggar Valley and the cultural sequences in different parts of North India suggest that PGW developed in the Ghaggar Valley. However, it is important to repeat that PGW did not have direct relations with the Bara‐style pottery which was widespread in the preceding period but had connections with the black ware industry in the Ganga Valley. Therefore, the origin of PGW must be searched in its relations with the black ware industry in the east, that is in the connection between the Ghaggar Valley and the Ganga Valley during the second millennium BCE

NBPW has been known not only from North India but also different parts of South Asia, but the Early phase can be attested only in the eastern Ganga Valley. As discussed in the preceding sections, the eastern Ganga Valley is a region where the black ware tradition developed for several millennia, and NBPW was part of this black ware tradition of this region. The excavations at Rajghat (Narain and Roy 1976) and Prahladpur (Narain and Roy 1968) stratigraphically exhibit the predominance of BSW just before the emergence of NBPW indicating the process of the generation of NBPW.

The evidence examined in this paper strongly exhibits that PGW continued to the midfirst millennium BCE and had a relationship with NBPW in the eastern Ganga Valley. While further examination must be made to fully understand the relationships between PGW and NBPW, it is evident that a wide area including the Ganga Valley and the Ghaggar Valley formed an interaction system in this period as in the preceding period. During the late first millennium BCE, PGW faded out from North India, and the ʹcoarseʹ variety of NBPW and its associated red ware penetrated the Ghaggar Valley.

Tuesday, 11 October 2022

The Sintashta died young, but had a lot of children?

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajhb.23129

Results

Lesions were minimal for the KA-5 and MBA-LBA groups except for periodontitis and dental calculus. No unambiguous weapon injuries or injuries associated with violence were observed for the KA-5 group; few injuries occurred at other sites. Subadults (<18 years) formed the majority of each sample. At KA-5, subadults accounted for 75% of the sample with 10% (n = 10) estimated to be 14-18 years of age.

Conclusions

Skeletal stress markers and injuries were uncommon among the KA-5 and regional groups, but a MBA-LBA high subadult mortality indicates elevated frailty levels and inability to survive acute illnesses. Following an optimal weaning program, subadults were at risk for physiological insult and many succumbed. Only a small number of individuals attained biological maturity during the MBA, suggesting that a fast life history was an adaptive regional response to a less hospitable and perhaps unstable environment.

Sunday, 9 October 2022

The Fatyanovo were swarthy & not lactose tolerant

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abd6535

The presented genome-wide data are derived from 3 Stone Age HGs (WeRuHG; 10,800 to 4250 cal BCE, BER001, KAR001, PES001) and 26 Bronze Age Fatyanovo Culture farmers from western Russia (Fatyanovo; 2900 to 2050 cal BCE) and 1 Corded Ware Culture individual from Estonia (EstCWC; 2850 to 2500 cal BCE)

In the case of radiocarbon dating, it is possible that fish from rivers and lakes consumed by Stone Age fisher-hunter-gatherers may cause a notable reservoir effect. This means that the radiocarbon dates obtained from the human bones and teeth can be hundreds but not thousands of years older than the actual time these people lived (33). Unfortunately, we do not yet have data to estimate the size of the reservoir effect for each specific case. Then, we turned to the Bronze Age Fatyanovo Culture individuals and determined that they carry maternal (subclades of mtDNA hg U5, U4, U2e, H, T, W, J, K, I, and N1a) and paternal (chrY hg R1a-M417) lineages (Table 1, fig. S1, and tables S2 to S4) that have also been found in CWC individuals elsewhere in Europe (14–16, 18, 27). In all individuals for which the chrY hg could be determined with sufficient depth (n = 6), it is R1a2-Z93.

The Fatyanovo are the most likely candidates for pre-Proto-Indo-Iranians, representing the earliest stage Pre-Proto-IIr splitting up from what would be Proto-Balto-Slavic.

We estimated the time of admixture for Yamnaya and EF populations to form the Fatyanovo Culture population using DATES (37) as 13 ± 2 generations for Yamnaya Samara + Globular Amphora and 19 ± 5 generations for Yamnaya Samara + Trypillia. If a generation time of 25 years and the average calibrated date of the Fatyanovo individuals (~2600 cal BCE) are used, this equates to the admixture happening ~3100 to 2900 BCE.

The confidence intervals (CIs) were extremely wide with Trypillia, but the chrX data showed 40 to 53% Globular Amphora ancestry in Fatyanovo, in contrast with the 32 to 36% estimated using autosomal data. The sex-biased admixture is also supported by the presence of mtDNA hg N1a in two Fatyanovo individuals—an hg frequent in Linear Pottery Culture (LBK) EFs but not found in Yamnaya individuals so far

The Fatyanovo were formed as a result of the process of Yamnaya male invaders taking European farmer women as wives, resultant genome being 2/3 Yamnaya and 1/3 EEF. The chrX data is based on a horribly low 45k snps so I will take it with a grain of salt, but the Y-DNA makes it somewhat clear still.

Outgroups used in the study: Mota, Ust-Ishim, Kostenki14, GoyetQ116, Vestonice16, MA1, AfontovaGora3, ElMiron, Villabruna, WHG, EHG, CHG, Iran_N, Natufian, Levant_N, and Anatolia_N

Wednesday, 5 October 2022

The diverse genetic origins of a Classical period Greek army

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2205272119

Here, we analyze genome-wide data from 33 individuals associated with the Battles of Himera and from Himera’s civilian population, as well as 21 individuals from two nearby settlements associated with the indigenous Sicani culture of Sicily, to provide insight into the genetic ancestry of Sicily’s inhabitants in the first millennium BCE and to provide additional data points for evaluating the role of ancient conflict in population interactions in the ancient Mediterranean.

Using qpAdm, this group (Sicily_IA, new data) can be modeled as an admixture of four sources that distantly contributed to the genetic composition of Europeans (P = 0.179):

Northwestern Anatolian Neolithic farmers (Turkey_Barcin_N; 76.4 ± 1.2%), WHGs (6.4 ± 1.0%), early farmers from Iran (Iran_GanjDareh_N; 6.3 ± 1.5%), and Early Bronze Age (EBA) Steppe herders associated with the Yamnaya cultural complex (Russia_Samara_EBA_Yamnaya; 10.9 ± 1.6%), which indicates an increase of Iranian-related admixture compared with the preceding LBA Sicily group, which can be best modeled without that component. One line of evidence for some local genetic continuity is the almost exclusive presence of Y-chromosomal haplogroup G-Z1903 and its derivates among the males.

Most Himerans associated with the battles can be found clustering on the PCA closely with individuals from the Greece_LBA, consistent with a major contribution of individuals of primarily Greek ancestry in the Himeran forces and substantial genetic continuity between the LBA period in Greece and fifth-century-BCE Greek colonies in Sicily. Seven of the 16 soldiers of the 480 BCE battle (Sicily_Himera_480BCE_1) and all 5 of the soldiers of the 409 BCE battle (Sicily_Himera_409BCE) are part of this main genetic cluster. Using the qpWave/qpAdm framework, we can model each of the soldiers in these two groups as deriving their ancestry either 100% from a group related to Greece_LBA or from an admixture between a Sicilian LBA or IA source and an Aegean-related source

One irritating thing about this unsupervised ADMIXTURE run is they label the Euro HG component as WHG and not EHG. This will obviously have funny results when trying to find non-local ancestry, especially from Northeastern Europe or the Steppes, like Baltic_IA showing up as 50% "WHG"

Looks like the non-outlier Himerian soldiers can be modelled as a mix of Aegean_BA + Sicily_LBA/IA, somewhat bolstering the idea that these Himerians were descendants of Greek colonists mixed with the local Sicilians.

Two individuals (I10943/W0396 and I10949/W0403; Sicily_Himera_480BCE_3) fall with modern northeastern European groups and eastern Baltic populations of the first millennium BCE and can be modeled using exclusively BA individuals from Lithuania as a proxy source (P = 0.129).One low-coverage individual, I17870/W0336, falls intermediate between Sicily_Himera_480BCE_2 and Sicily_Himera_480BCE_3 on both PCA and with respect to the main ancestry clusters inferred from ADMIXTURE.Two (I10944/W0461 and I10947/W1774; Sicily_Himera_480BCE_4) fall with individuals from IA nomadic contexts in the Eurasian Steppe. In qpAdm, their ancestry is consistent, with around 85–89% deriving from IA Central steppe nomads and 11–15% from an Aegean-like source, an admixture that plausibly could have taken place among the genetically diverse populations of the Steppe. Their mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups suggest east Eurasian genetic roots: A6a, found so far only in modern-day China (70, 71), and N1a1a1a, restricted to Russia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia.Finally, one outlier (I10951/W0653; Sicily_Himera_480BCE_5) falls with modern Caucasus populations and intermediate to ancient Steppe and Caucasus individuals on the PCA and carries the highest proportion of the CHG component in ADMIXTURE (Fig. 2). A single one-way model with a group closely related to Armenia_MBA as the source fit the data (P = 0.293). Similarly, the second low-coverage individual, I17872/W0428, falls closest to populations from the Caucasus on the PCA .

Now, for the outliers.. Won't be surprised if I10944 and I10947 were Sarmatians, they have the typical East Eurasian mtDNA plus slight East Asian DNA (10-15%) in amounts typical of Sarmatians and Cimmerians.

All the soldiers who fall outside the Aegean genetic cluster are interred in mass graves Nos. 1–4 (SI Appendix, Figs. S1–S3), whereas all individuals from mass graves Nos. 5–7 (SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S6) fall within this cluster, a statistically significant difference (P = 0.0028 by a χ2 test with one degree of freedom; Fig. 3). This result mirrors strontium isotope evidence showing more nonlocals interred in mass grave. Mass graves Nos. 1–4 and Nos. 5–7 also are spatially segregated and differ in size, with mass graves Nos. 1–4 comprising significantly more interments.Furthermore, individuals in mass graves Nos. 5 and 6 include grave goods, unlike the other mass graves from 480 BCE (32). The fact that these individuals also fall within the Aegean genetic cluster suggests a link between Aegean ancestry and prestige, as perceived by the individuals responsible for burying the fallen soldiers.Individuals with “foreign” ancestry, all of whom also are identified as nonlocal on the basis of isotopic evidence (Fig. 3 and Dataset S2), were interred in larger mass graves Nos. 1–4, and individuals with genetic affinities to other Greek populations were interred in the smaller mass graves Nos. 5–7

It looks like the local soldiers, who were of Aegean descent, were given more prestigious burials than the non-local ones.

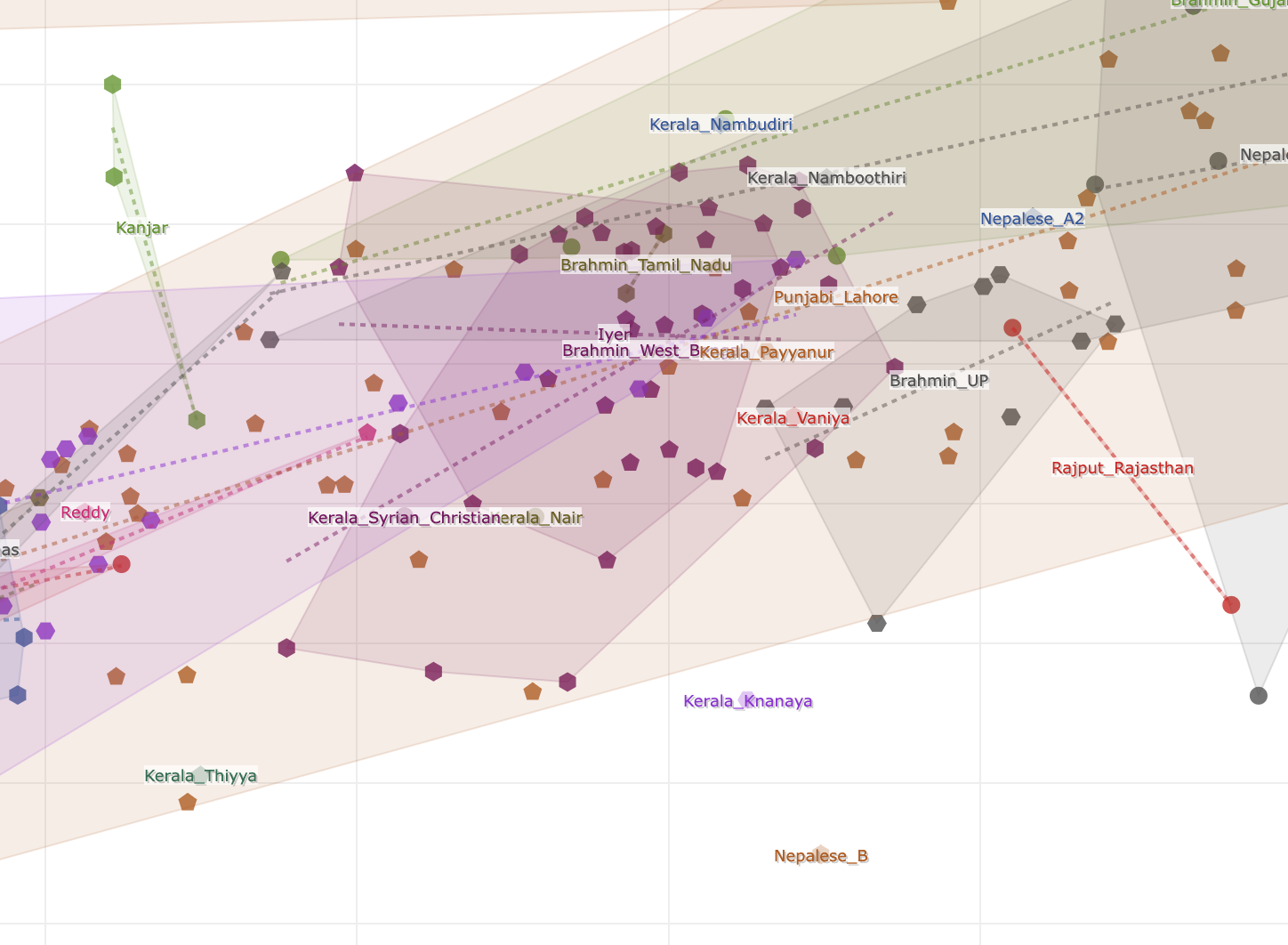

The Indo-Iranian cline.

Further right, we see the North-West Brahmin cluster, which is more Steppe/West Eurasian shifted than the generic UC cluster, and has Brahmins from Jammu, Himachal, Kashmir and Gujarat, clustering along with some Punjabi Hindus and NepaleseA (likely Nepali Brahmins).

To the right of this, we get the North West Indo-Pakistani cluster, which contains the most Steppe and Eurasian shifted groups in the subcontinent. Notice how the Rors and Kalash lie a little distinct from this cluster too. The Kalash do not have that much Steppe ancestry (25%) but they do have a lot of Siberian/Turanian ancestry from Bronze Age groups such as Aigryzhal_BA, and actually the Kalash are shifted towards them on the PCA. This becomes more clear when we see a 3D PCA (the one posted here is 2D unfortunately).

Maratha & Chitpavans

Marathas seem to have a lot of variation in their Andronovo and AASI ranges. Perhaps this is a confirmation of the fact the modern Maratha c...

-

The Kurmi are a Shudra caste of non-elite tillers and reside mostly in the North Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Something cool ...

-

In South Asian genetics, we suffer from a paucity of ancient DNA to study. We have about 100 samples from Pakistan, Gandhara to be precise. ...

-

Below is a custom-PCA that shows us the genetic variation in modern Indo-Iranians. Let us make some observations. The left-right PC1 cline s...